In this blog post, I would like to “introduce” you to our introduction style. Writing the introduction is the most daunting part of the paper writing process, especially for students who are not native english speakers. To help structure the introduction writing process, in our lab we have developed a standard style or template for writing introductions. Since the majority of the papers that we write are papers that describe new computational methods, many of our papers naturally fit into this style. We usually publish our papers in Genetics journals which have very high standards of writing and are read by researchers with a wide range of backgrounds. The difference between a paper getting accepted and rejected is often determined by the clarity of the writing.

Our introduction style is a very specific formula that works for us but obviously there are other ways to structure an introduction and each experienced writer will have their own style. However, the truth is, you NEVER start out as a good writer and new writers need to start somewhere. It takes practice, consistency and effort to write well. If you are a new writer apprehensive about writing an introduction, we hope that this structure can help you.

Our introductions are typically four paragraphs long with each paragraph serving a specific role:

1. Context – First, it is important to explain the context of the research topic. Why is the general topic important? What is happening in the field today that makes this a valid topic of research?

2. Problem – Secondly, you present the problem . We typically start this paragraph with a “However,” phrase. Simple example: We have this awesome discovery in XYZ… However, using former methods it will take us 10 years to run the data. Each sentence in this paragraph should have a negative tone.

3. Solution – By this point, your readers should sympathize with how terrible this problem is and how there MUST be a solution (maybe a little dramatic, but you get my point). Paragraph three always starts with “in this paper” and a descritpion of what the paper proposes and how it solves the problem in the second paragraph.

4. Implication – The last paragraph in your introduction is the implication, which describes why your solution is important and moves the field forward. Typically, in this paragraph is where you summarize the experimental results and how they demonstrate that the solution solves the problem. This paragraph should answer the readers question of “so what?”.

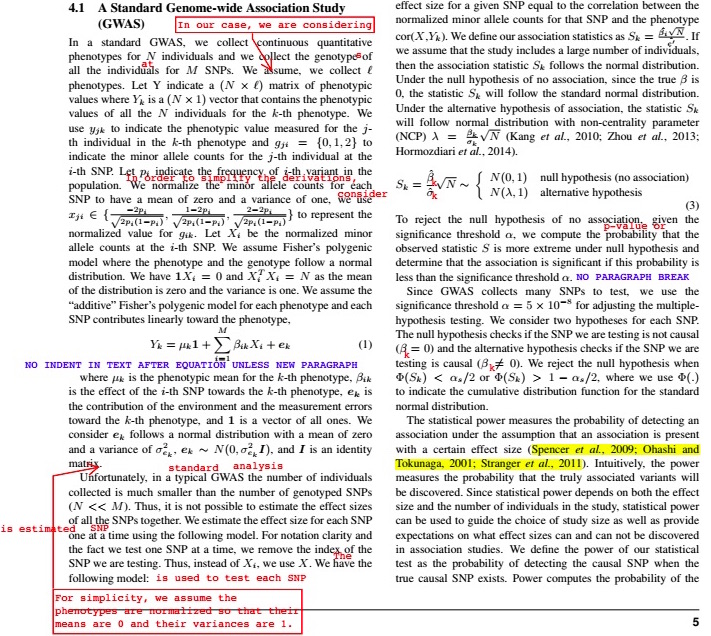

An example of the 4 paragraph introduction style is in the following paper:

Most of our other papers in their final form do not follow this format exactly. But many of them in earlier drafts used this template and then during the revision process, added a paragraph or two expanding one of the paragraphs in the template. For example, this paper expanded the implication to two paragraphs:

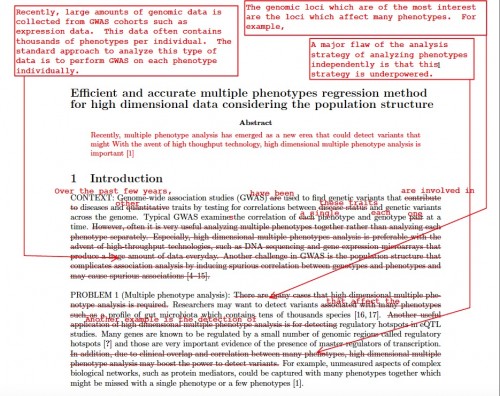

and this paper expanded both the context and problem to two paragraphs each:

For methods papers, sometimes what are proposing is an incremental improvement over another solution. In this case, moving from the context to the problem is very difficult without explaining the other solution. For this scenario, we suggest the following six-paragraph structure:

Context

Problem 1 (the BIG problem)

Solution 1 (the previous method)

Problem 2 (Why does the previous method fall short?)

Solution 2 (“In this paper” you are going to improve Solution 1)

Implication

An example of 6 paragraph introductions where the 3rd and 4th paragraph were merged is:

There it is… the beginning to a great paper (at least we like to think so!). Will this work for you? Have other ideas? Let us know in the comments below!