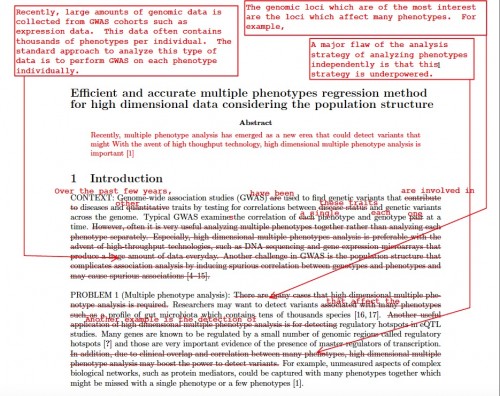

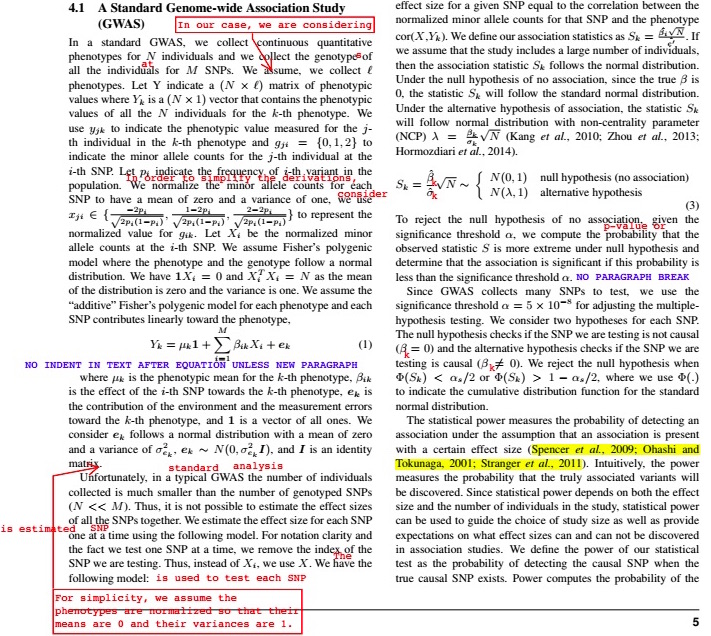

This is an example of our edits. The red marks are directly edits and the blue are high level comments.

In our last writing post, we talked about how our group of a dozen undergrads, four PhDs and three postdocs (not to mention our many collaborators) stays organized. This week we would like to focus on our paper writing process, and more specifically, how we edit.

Believe it or not, each one of our papers goes through at least 30 rounds of edits before it’s submitted to be published. You read that right… 30 rounds of edits. Each round is very fast with usually a day or two of writing, and we try to give back comments within a few hours of getting the draft. Because we are doing so many iterations, the changes from round to round often only affect a small portion of the paper. The writing process begins in week one of the project. This is because no matter how early we start writing, at the end of the project, our bottleneck is the paper is not finished even though all of the experiments are complete. For that reason, starting writing the paper BEFORE the experiments are finished (or even started) leads to the paper being submitted much earlier. Some people feel that they shouldn’t write the paper until they know how the experiments are finished so they know what to say. I completely disagree with this position. I think it is better to start at least with the introduction, overview of the methods, the methods section, the references etc. If the experimental results are unexpected then the paper can be adapted to the results later. However, getting an early start on the writing substantially reduces the overall time that it takes to complete the paper.

To jump start the students writing, I sometimes ask them to send me a draft every day. We call this “5 p.m. drafts.” Just like we mentioned in our very first writing tips post, the best way to overcome writer’s block is to make writing a habit. What I find is that if I get a draft that is one day of work or a week of work from a student, it still needs the same amount of work. This is what motivates our writing many many many iterations.

Editing in our lab is certainly not done in red ink on paper. That would be WAY too difficult to coordinate the logistics. The way we do it is via a PDF emailed from the students. I edit it on my iPad using the GoodReader app, which can make notes, include text in callouts, draw diagrams and highlight directly on the document. GoodReader also lets me email the marked PDF back to the students directly. It typically takes 30 minutes to an hour to make a round of edits. This inexpensive iPad app has increased our workflow and decreased our edit turnaround significantly. Keep in mind that I don’t always need to make a full pass on the paper, but just give enough comments to keep the student busy during the next writing period (which can be one day).

Since my edits are marked on the PDF, the students needs to enter the edits into the paper. This is great for them as they get to see the edits and this improves their writing. Previously, when I would make edits on the paper directly, they wouldn’t be able to see them. When I edit, I make direct changes in red and general comments in blue.

Like our method? Let us know!